- Reproduction

- InventarnummerCOMWG.368

- Hersteller

- Titel

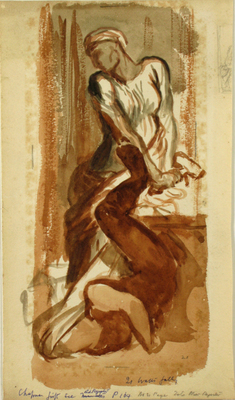

Jael, Watercolour Study

- Datumcirca 1862 - 1863

- Medium

- Format

- drawing height: 32 cm

drawing width: 19 cm

mount height: 56 cm

mount width: 40.5 cm - Beschreibung

This work is a watercolour study for ‘Jael’ (c. 1862-65) in monochrome of a draped female figure wearing a head covering standing over a male figure who lies twisted on the floor. In the Book of Judges, the seventh book of the Old Testament, there are three deaths that are caused by women: the killing of Abimelech, Delilah’s betrayal of Samson, and the murder of Sisera by Jael, as told in Judges 4-5. Sisera was the captain of the King of Canaan Jabin’s army, who oppressed the Israelites for twenty years. Sisera’s death was prophesised by the prophetess Deborah who was the only female judge of Israel. She instructs the commander Barak that he should meet the army of King Jabin at Mount Tabor and that Sisera will be defeated by the hand of a woman. Jabin’s army is indeed overpowered and Sisera flees to seek refuge in the tent of Jael, the wife of Heber the Kenite. She invites him into her tent, covers him with a mantle, and gives him milk to drink. But as Sisera is lulled to sleep, Jael kills him by hammering a nail from the tent into his temple. As Barak comes to the tent seeking Sisera Jael shows him to her victim. The killing of Sisera signals the end of King Jabin’s rule over the Israelites.

As scholars have noted, the Killing of Sisera speaks to the heart of questions surrounding female authority, emancipation, and equality. By killing Sisera of her own volition Jael goes against her husband, who is at peace with Jabin. Hence, this episode and its female protagonists have inspired artists, writers, and musicians for centuries, and continues to do so today [1]. While the prophetess Deborah is mostly depicted as a heroic authoritative figure and a positive example of female leadership, Jael’s violence has inspired more conflicting, often ambiguous, interpretations. As Anne W. Stewart notes, Jael is either depicted ‘as a victorious woman, violently administering Sisera his just deserts, or as a seductive temptress, stealthily maiming the sleeping warrior’ as seen in the work of Artemisia Gentileschi [2]. She is either a heroine inspired by God, or an evil temptress.

In the nineteenth century, such a story of false hospitality and domestic comforts ‘came unnervingly close to home’, Peter Merchant argues, provoking a peculiarly Victorian anxiety about the angel in the house transformed into a murderess [3]. But it was also a narrative of female emancipation. In the nineteenth century, as women began to challenge ‘the limits of their societal roles’, the binary response to Jael’s actions began to be reimagined and questioned [4]. Charlotte Brontë likened the repressed Lucy Snowe to Jael in Villette (1853), and George Eliot has Maggie Tulliver re-enact the killing of Sisera in The Mill on the Floss (1860) as a direct expression of her frustration with societal expectations of her gender. In Anthony Trollope’s The Last Chronicle of Barset (1867) the murder is discussed in the subplot that sees the artist Conway Dalrymple paint Jael and Sisera. In 1873, Tennyson’s friend Lord de Tabley’s wholly Victorian Jael in his poem ‘Jael’ finally explicitly asked the Woman Question [5].

It is difficult to ascertain whether Watts intended to depict Jael as a heroine or seductive evil murderess. Yet, one sees traces of such a complex and rich tradition in this compositional sketch by Watts. It is very different from the earlier work of for example James Northcote’s Jael and Sisera (1787). The draped figure of Jael is more reminiscent of Gustave Doré’s Bible illustrations (1866), and there is a likeness too in how the twisted body of the defeated general rests at her feet. Her head covering also suggests a possible connection to the work in sculpture by G. F. Watts’s contemporary Alfred Stevens (1817-1875). Between 1862 and 1865, Stevens was working on designs intended for the redecoration of St Paul’s Cathedral, which included two figures of Judith and Jael respectively [6]. G. F. Watts was involved with this project as well.[7]. There is also an interesting connection between Watts’s portrayal of the threatening Jael and the sculpture of Jael by the Scottish W. C. Marshall, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1867. One reviewer noted the disturbing portrayal of the ‘miserably attenuated and painfully distorted figure’ which recalls Watts’s uncompromising depiction of Jael [8].

Watts’s painting of Jael, with a striking green background, was never exhibited. Yet it deserves our attention as a multifaceted contribution to an important debate which continues to this day. It is also a sign of Watts’s deep knowledge of the Old Testament. Jael is one of several compositions inspired by the Book of Judges, such as Samson (COMWG.75, 1871).

Explore:

Sketchbook of G. F. Watts, navy blue with silver clasp (COMWG2007.200)

Footnotes:

[1] For a cultural history of the figure of Jael see Colleen M. Conway, Sex and Slaughter in the Tent of Jael: A Cultural History of a Biblical Story (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017). See also Celia Wallhead, ‘The Story of Jael and Sisera in Five Nineteenth- and Twentieth- Century Fictional Texts’ in Atlantis 23.3 (2001), pp. 147-166.

[2] Anne W. Stewart ‘Deborah, Jael, and their Interpreters’, in Women’s Bible Commentary: Revised and Updated ed. by Carol Ann Newsom, Sharon H. Ringe, and Jacqueline E. Lapsley (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2012), pp. 128-132, p. 131.

[3] Peter Merchant, ‘Inhabiting The Interspace: De Tabley, Judges, “Jael”’, in Victorian Poetry 36.2 (1998), pp. 187-204, p. 187.

[4] Colleen M. Conway, ‘Motives for Murder in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Cultural Performances of Jael and Sisera’ in Sex and Slaughter in the Tent of Jael: A Cultural History of a Biblical Story (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 90-119, p. 90.

[5] Ibid., p. 93.

[6] D. S. MacColl, ’The Stevens Memorial and Exhibition at the Tate Gallery’ in The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 20.104 (1911), pp. 111-117.

[7] Hilary Underwood, Parables in Paint: An Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings from the Collection of Watts Gallery St Paul’s Cathedral, London (Compton: Watts Gallery, 2008).

[8] ‘The Royal Academy Exhibition: Article III.-Sculpture’ in The Building News and Engineering Journal 14 (1867), pp. 371-372, p. 371.

Text by Dr Eva-Charlotta Mebius

|

|