- Object numberCOMWG.67

- Artist

- Title

Prince de Joinville

- Production date

- Medium

- Dimensions

- Painting height: 61 cm

Painting width: 50.8 cm - Description

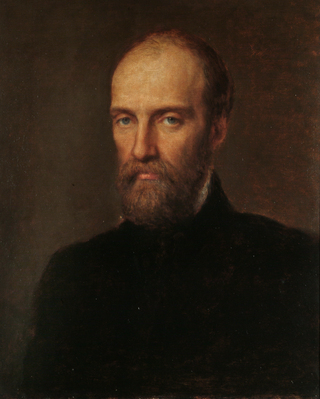

A portrait of an exiled Prince. François d’Orléans, Prince de Joinville (1818–1900) was the third son of King Louis Philippe I of France. Following the revolution of 1848, the family were exiled and travelled to England where they set up their temporary home at Claremont House, Surrey at the invitation of Queen Victoria until 1861. According to Mary, the forlorn expression of the Prince and the attention given to the eyes in this portrait is a result of the Prince’s deafness which he had suffered from since his early twenties.

- In depth

I have from boyhood belonged to the French Navy’ wrote the Prince de Joinville in 1853 [1]. AS the third son of King Louis Philippe of France and Queen Marie-Amelie, François-Ferdinand-Philippe-Louis-Marie d’Orléans, to give him his full name had forged a career as a notable admiral in the French Navy from an early age. At 18 he became a lieutenant and two years later he led a bombardment at San Juan de Ulloa where he took the Mexican general as prisoner. After quickly being promoted to captain, in 1840 the Prince was then entrusted with a great honour as he was given the responsibility of bringing the remains of Napoléon from Saint Helena to France. His naval career however was cut abruptly short in 1848 due to the revolution when his father abdicated the throne and the royal family fled in England in exile.

By invitation of Queen Victoria, the family resided at Claremont House in Surrey. The King himself died there in the summer of 1850 but the rest of the family remained until 1861. During this time the Prince continued to publish essays and pamphlets on naval affairs. His bombastic approach to reporting events often inciting opposition and irritation amongst British press who concluded on more than one occasion that although ‘unable to earn his epaulettes with the sword, [the Prince] is valiant with the pen; and what reality denies, the Prince achieves with his imagination’ [2].

His need to have his voice heard may have been a result of the Prince’s deafness which had become an increasing disability since his early 20s. In 1847, the French poet and novelist Victor Hugo, who was well acquainted with the family commented that whilst ‘sometimes it saddens [the Prince], sometimes he makes light of it. One day he said to me: "Speak louder, I am as deaf as a post"’ [3]. It is the Prince’s deafness which Mary attributes to ‘the earnest attention’ of his blue eyes as he stares out at the place in which Watts would have been positioned when he painted him [4].

It is not known when this portrait was painted. It is possible that Watts painted it towards the end of the Prince’s stay in England. Whilst the royal family had sought refuge at Claremont House in Surrey, Mary details how they were also ‘welcomed guests’ at Holland House and it was here that Watts ‘saw much of these Princes who were very cordial to him’ [5]. In photographs of the Prince from c.1861, when he would have been aged around 43, his full bushy beard which gave the impression of a longer face, and his receding hair line, high on his forehead are evident. Whereas at the beginning of the previous decade, when the family first arrived in Britain, the Prince was depicted as clean shaven.

Another indicator that the portrait may have been painted in the early 1860s is the support on which it is painted. From 1858 until c.1870 Watts painted a number of portraits on panel including: Dr Demetrius Zambaco (COMWGNC.20, 1858), Lord Campbell (COMWG.18, 1860;), Lady Somers (COMWG.71, 1860), Double Portrait of Long Mary, (COMWG.180), and Earl of Shrewsbury (COMWG.52, 1862 ) and so it is likely that the portrait of the Prince was also painted during this phase of his practice.

Compositionally it is similar to Watts’s ‘Hall of Fame’ portraits which were often bust-length portraits of a male sitter, painted in three-quarter profile against a dark background, wearing non-descript clothing. Although a royal, the Prince does not wear any emblems or decoration to demonstrate his status. This portrait, however, would not have been accepted to the National Portrait Collection, and along with the other portraits that Watts painted of foreign men of note including those of Joseph Joachim and Giuseppe Garibaldi, this portrait remained in his private collection.

Footnotes:

[1] As quoted in ‘The Prince de Joinville and Captain Townshend’, Examiner, 26 February 1853, p.132.

[2] ‘The Prince de Joinville’, Examiner, 25 May 1844, p.323.

[3] Victor Hugo, The Memoirs of Victor Hugo (1899), p. 152.

[4] Mary Seton Watts, Catalogue of Portraits by G.F. Watts O.M. R.A., Vol. I, c.1915, p.81.

[5] Mary Seton Watts, Catalogue of Portraits by G.F. Watts O.M. R.A., Vol. I, c.1915, p.81.

Further Reading:

‘The Prince de Joinville’, Examiner, 25 May 1844, p.323.

‘The Prince de Joinville and Captain Townshend’, Examiner, 26 February 1853, pp.131-132.

Victor Hugo, The Memoirs of Victor Hugo (1899)

Harry G. Lang, ‘A Deaf Prince in Art and War: The Prince de Joinville, French exile and military advisor’, Military Images, vol. 35, no. 3 (Summer 2017), pp.74-78.

Mary Seton Watts, Catalogue of Portraits by G.F. Watts O.M. R.A., Vol. I, c.1915.

Text by Dr Stacey Clapperton

|

|