- Reproduction

- Número del objetoCOMWG2007.317

- Creador

- Título

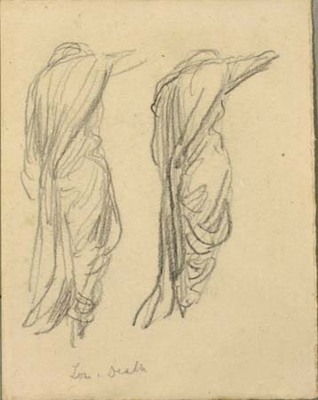

Double Pencil Study of the Figure of Death for 'Love and Death'

- Fechacirca not before 1871 - circa not after 1887

- Medium

- Dimensiones

- drawing height: 11.7 cm

drawing width: 9.1 cm

mount height: 52.4 cm

mount height: 41 cm - Descripción

Double Pencil Study of the Figure of Death for 'Love and Death'-both sketchy drawings showing the same composition with the draped figure from the back, proper right arm outstreched to the right and forwards and the draped head leaning forward; the study on the right slightly smaller and blacker; pencil inscription in old hand underneath the drawings 'Love and Death'-composition similar to the finished oil painting (Tate version); studies of the draped figure for the allergorical (symbolist) picture

Mary Watts shared many of G.F. Watts’s thoughts on this work. She noted that Watts struggled with this piece and finally changed the gesture Death makes, thereby changing the connotation of this work. She stated:

every line, and the character of every line, of the various parts was pondered over, sometimes during many years. On his return home, when the second version of the " Love and Death " upon a large scale was first brought out and put upon his easel, he saw that, owing to some subtle changes in line and tone, the figure of Death had neither the weight nor the slow movement he desired to give it. So day after day he thought and toiled, and I saw each fold of the garment deliberately reconsidered, a hair's-breadth of line or a breath of colour making the difference that a pause or an accentuated word would make in speaking. For instance, by raising the hand and outstretched arm a less judicial and severe impression was conveyed, and by this slight alteration the action changed from ‘I shall’ to the more tender ‘I am compelled’ [1].

Here Mary points out the gesture of Death in this drawing, and how this version extends their right arm as opposed to other drawings that possess a lowered right arm curled around a scythe. With this change in the arm’s direction Mary notes that the figure is compelled to take this action against the figure of love standing in the doorway.

Mary also shares a history of this work and Watts’s thoughts on it. In the catalogue she compiled of Watts’s work she listed eleven different versions of this work [2]. Regarding the version displayed at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1881 Mary notes that Watt’s stated, “love here is the love that illuminates the house of life” [3]. Mary is, therefore, confirming the Symbolist interpretation of scholars, such as Trodd, who argues that this work shows Love trying to block Death from entering [4]. Mary records that G.F. Watts offered a further comment on the 1875 version when he stated, “I consider it my best work hitherto, I have been bestowing great labour and thought upon it” [5]. Here Mary confirms not only that Watts thought a lot of this work, but considered it his best up to that point.

Contemporaries of Watts also praised this work as one of his best for different reasons. When describing this work G.K. Chesterton wrote, “Love and Death is truly a great achievement: if it stood alone it would have made a man great… For the whole picture really hangs, both technically and morally, upon one single line, a line that could be drawn across a blank canvas,”. [6]. Hugh Macmillan highlighted the qualities of this work. He stated, “"Love and Death," for instance, is instinct throughout with the best influences of Pre-Raphaelitism — the novel and striking treatment of a great subject — the beautiful composition and colour — the wonderful power and clearness of all the details” [7]. Although both of these authors praise this work they base their admiration on different reasons. While Macmillan mentions the subject, he focused more on the details while Chesterton examined both the technical qualities and the message conveyed by the work

Like Mary Watts and Chesterton, other Watts’s scholars also highlight the Symbolist qualities of this work. Authors such as Phythian, Barrington, Staley, Bills, Bryant, Trodd, and many others note how Watts drew inspiration for this work based on a portrait Watts was painting of a young nobleman who was dying from an incurable disease. Barrington describes how the figures in this work represent this idea by noting:

The solemn figure moves forward notwithstanding, as it were inevitably, rather than as if forcing a way; a fatal doom, against which the struggles of Love are in vain. Death overshadows his figure, except where a few bright rays of colour still light on his brow, on the roses which wreathe it, and on the arm which clings still to the doorway. In his anguish he gazes appealingly up into the face of the awful stranger, while with his outstretched arm he attempts to resist advance [8].

Barrington highlights this Symbolist interpretation by noting how the figures represent Death and Love with the latter trying to stop Death from entering this door.

Footnotes:

[1] Mary Watts, The Annals of an Artist’s Life, Volume 2, pages 86-87.

[2] Mary Watts, Catalogue of the Works by G.F. Watts, pages 88-91.

[3] Mary Watts, Catalogue of the Works by G.F. Watts, pages 89.

[4] Colin Trodd, “Before History Painting: Enclosed Experience and the Emergent Body in tthe Work of G.F. Watts,” Visual Culture in Britain 6 (2005), page 39.

[5] Mary Watts, Catalogue of the Works by G.F. Watts, pages 88.

[6] G.K. Chesterton, G.F. Watts, page 64.

[7] Hugh Macmillan, The Life-work of George Frederick Watts, R.A., page 7.

[8] Mrs. Russell Barrington, G.F. Watts, Reminiscences, page 134.

Text by Dr Ryan Nutting

|

|