- Reproduction

- Numero oggettoCOMWG2007.486a

- Creatore

- Titolo

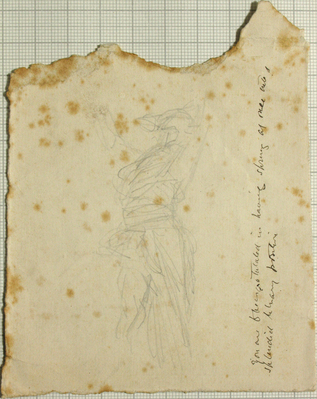

Pencil Study of a Standing Draped Male Figure-Study for 'Jonah'

- Data

- Materiale

- Dimensioni

- drawing height: 12.1 cm

drawing width: 9.8 cm - Descrizione

This small sketch by G. F. Watts is a study for one of his most divisive paintings Jonah, also known as Jonah Prophesying against Nineveh (1894) illustrating the Book of Jonah of the Old Testament. Famously, at first, having received the task of crying out against the iniquities of Nineveh, Jonah fled from the responsibility and ended up being swallowed by a whale (or large fish), in which he spent three days and nights. Jonah prayed to be let out, upon which God forgave him. Having escaped the bowels of the fish Jonah went to Nineveh to prophesy the cities imminent downfall upon which the people of Nineveh repented (Jonah 1-4). It was a relatively rare subject. Other nineteenth-century works of art that depicted scenes from the Book of Jonah at the Royal Academy included Henry Singleton’s (1766-1839) Jonah Waiting the Fate of Nineveh (1815), the Scottish painter William Allan’s (1782-1850) The Prophet Jonah (1829), H. L. Smith’s (1809-1870)- Jonah’s Impatience Reproved (1845), and wood engravings by William J. Linton (1812-1897) of Gustave Doré’s (1832-1883) Jonah (1863).

As the architect, critic, and editor Henry Heathcote Statham (1838-1924) argued in 1901, it ‘should be a warning to artists, to observe how inevitably Biblical subjects seem to be synonymous with mediocrity and commonplace in painting’ [1]. However, he did not include G. F. Watts’s biblical paintings in this category. Rather, in his review of an exhibition at Burlington House, Heathcote Statham recalled that the ‘only Bible-picture of late years which showed real force and reality of conception was Mr. Watts’s’ figure of Jonah which he considered to be ‘too real for an orthodox Bible illustration’ [2]. From this small fragment of a sketch it may be difficult to understand the power and disturbing presence of Watts’s Jonah, who prophesises with his arms outstretched similar to a conductor guiding an orchestra. But it is possible to get an idea of the powerful, striking pose from this twisted draped figure reminiscent of Michelangelo’s fresco depicting Jonah from the Sistine Chapel

Jonah was first exhibited at the Royal Academy of 1895, when it was described as a ‘picture that can never be forgotten’ [3]. The unforgettable picture stood out among Biblical pictures by F. A. Bridgman (1847-1928), Albert Goodwin (1845-1932), W. B. Richmond (1842-1921), J. W. Waterhouse (1849-1917), E. A. Fellowes Prynne (1854-1921), and J. E. Millias (1829-1896). The prominent Victorian art critic M. H. Spielmann was among those who praised the unconventional picture.

However, Spielmann and others also acknowledged that to ‘many it will be a repulsive picture; to all it must appeal as a perfectly natural expression of the passionate feeling which cried out against the wickedness and luxury that was hurrying a city to destruction, and which in its eternal truth might be addressed as well to our Babylon of to-day.’ [4] G. F. Watts would probably have agreed with this assessment, as the Assyrian reliefs that decorates the wall behind Jonah represented vices of Victorian times according to Mary Watts [5]. For M. H. Spielmann, Watts’s prophet recalled the figure of Solomon Eagle, the composer Solomon Eccles (1618-1683), who was mentioned in Daniel Defoe’s account of the plague of 1665 A Journal of the Plague Year (1722). In the nineteenth century, the prophet gained notoriety as one of the main characters in William Harrison Ainsworth’s (1805-1882) work of historical fiction Old St. Paul’s (1841) about the plague between 1665-1666 [6].

It was pictures such as this one that came to establish Watts as a prophetic figure in his own right. According to one obituary, it was what made him such a ‘singular’ figure, as Blake before him. Watts ‘took his office of painter as an Isaiah or an Ezekiel took his self-imposed office of prophet’ and labelled him ‘a great public functionary.’ [7] In her biography of her husband Mary Watts confirms this view of Watts as an apocalyptic prophet against ‘the present ideal’ of ‘all for self and self-advancement’ and worship of Mammon, prone to what she called his ‘Jonah-mood’ [8]. Perhaps Watts’s painting, then, was not only a biblical painting, but also a self-portrait.

Footnotes:

[1] H. Heathcote Statham, ‘The Loan Exhibition at Burlington House’ 69.411 (Mar, 1901), pp. 543-552, p. 550 See a photograph of the painting here: COMWG2007.841

[2] Ibid., p. 550.

[3] M. H. Spielmann, ‘The Royal Academy Exhibition.-II’ in The Magazine of Art (Jan 1895), pp. 281-284, p. 283. Spielmann was less convinced by Watts’s other prophetic picture which was shown at the same exhibition, Outcast Goodwill (COMWG.118, 1895) See also, Anon. ‘NOTES’ in Royal Academy Pictures: Illustrating the…Exhibition of the Royal Academy: being the Royal Academy supplement of The Magazine of Art (Jan 1895), pp. 4-8), and Anon. ‘The Salon and the Royal Academy’ in Saturday Review 79.2063 (May 11, 1895), pp. 616-618.

[4] Mary Watts Catalogue of Pictures, p. 83.

[5] See a chalk drawing of Solomon Eagle by Edward Matthew Ward R. A. (1816-1879) here: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/cdfnh62d.

[6] Anon. ‘G. F. Watts’ in The Athenaeum 4002 (Jul 9, 1904), pp. 53-54, p. 54.

[7] Ibid., p. 54.

[8] Mary Watts, George Frederic Watts Vol. II (London: Macmillan, 1912), pp. 148-149.

Text by Dr Eva-Charlotta Mebius

|

|