- Object numberCOMWG2007.408

- Artist

- Title

Five Ink Studies of Standing Female Nude Figures for the Left-Hand Side Goddess in 'Olympus on Ida', 1880s version

- Production datenot before 1880 - not after 1889

- Medium

- Dimensions

- drawing height: 12.8 cm

drawing width: 20.3 cm - Description

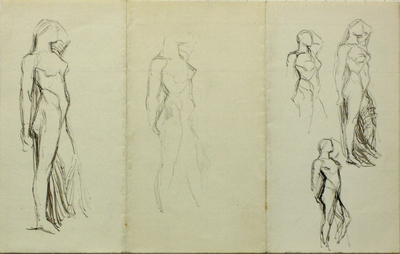

Five drawings of female nudes in the same position, facing right, show Watts’ efforts to perfect the pose of one of the goddesses in his painting Olympus on Ida. This figure is based on his studies from his favourite model, Long Mary, made in the second half of the 1860s. The drawings he made while she was a housemaid at Little Holland House served as reference material for the rest of his career. By the 1880s, Watts was involved in the Rational Dress movement in Britain. This campaigned against tightly laced corsets and promoted clothing for women that allowed freedom of movement. This drawing and its related paintings show Watts’ interest in athletic women’s bodies as the ideal, with visible muscles and a natural, uncorseted waist.

- In depth

This sheet shows five outline studies of the left-hand side goddess in Watts’ composition Olympus on Ida (COMWG.30, 1885), of which two painted versions and numerous drawing studies exist. [1] Watts’ first inspiration for the group was apparently suggested by the movement and shadow amongst bed hangings while he was laid up with an injury, preserved in an ink sketch at the Watts Gallery. The present sheet is among many others by Watts also held in the Watts Gallery- Artists' Village collection. It shows the far-left hand goddess, probably intended to be read as Athena, goddess of war, wisdom, and the arts. The subject of the finished work was a competition between the three most important Greek goddesses (Athena, Hera, and Aphrodite), to find who was the most beautiful and win a golden apple inscribed “to the fairest.” This subject allowed Watts to explore his idea of the ideal female nude at the height of his artistic powers in the 1880s.

Watts’ vision of the ideal female body within his work was unquestionably shaped by his long-term fascination, not to say obsession, with classical sculpture, particularly Greek. This drawing and the painting call to mind the Venus de Milo which had been discovered on Milos in 1820 and was displayed in the Louvre when Watts visited in 1843 and again in 1855 [2]. Casts were available at the Crystal Palace exhibition and Sydenham after 1851, and the Royal Academy had a cast for students [3]. The Venus de Milo was often held up as the epitome of the healthful, beautiful female body, and was often used as a positive example of the natural waist in arguments against corsetry and tightlacing [4].

Watts was an early supporter of the aesthetic and healthy dress reform movement for women. In 1883 he published an anti-tightlacing essay, ‘On Taste in Dress,’ and was elected President of the Norwood Anti-Tightlacing Society [5]. The movement advocated less-restrictive corsetry (although not the complete absence of support garments), garments which followed and articulated the natural line of the body without limiting movement, and often explicitly called on Greek and Roman drapery as the best example of rational dress. With Mary, he was a vice-president of the Healthy and Artistic Dress Union, founded in 1890, and worked on the movement’s journal Aglaia [6].

In the versions of Olympus on Ida, and other images of Long Mary in the nude, Watts emphasised her muscular, natural waist and abdomen, rather than the artificial lines of the period’s corsetry. These should not be considered portraits or accurate records; rather Watts used Mary’s body, or his recollection of it, as a template for the variations on his ideal. This includes visible musculature under the skin, long arms, legs, and neck, high breasts, and strong, regular facial features. Additionally, as Ken Montague notes in relation to the painting, Watts was inconsistent about where the waist, as the narrowest natural part of the body, actually fell on his three goddesses, something unlikely to change so dramatically on a real human body [7]. Watts incorporated elements of his ideal physical types from sources including the Parthenon sculptures the Venus de Milo, and Michelangelo, developing a muscular, often androgynous type similar to that of Edward Burne-Jones, Evelyn De Morgan, and Albert Moore.

This series of studies for the figure also demonstrates Watts’ repeat return to a vocabulary of gestures and poses throughout his career. In this sketch, and in the finished painting, the figure thrusts the arm closer to the viewer downward, holding it stiff and straight; the rear arm is lifted with the elbow pointing up and the hand tucked behind the head. This pose appears in Watts’ painting Dawn (untraced and known through a photograph by Frederick Hollyer) and the sculpture called Aurora (COMWG2007.957) in the collection of the Watts Gallery.

Footnotes:

[1] Art Gallery of New South Wales, Australia, inv. 20146P17; Buscot Park, Faringdon Collection, Cat. 87.

[2] Louvre, Paris, MA399.

[3] George Scharf, The Greek Court erected in the Crystal Palace (London: Crystal Palace Library and Bradbury & Evans, 1854) p. 49-50.

[4] Hallie M. Franks, ‘As Nature Formed It: Venus Sculptures and the ‘Natural’ Waistline in Dress Reform Discourse,’ Classical Receptions Journal Vol 13. Iss. 2 (2021) p.259.

As intellectual and artistic tastes shifted in the early nineteenth century to favour the more austere sculptural style of fifth-century Athens, the fame of the Venus de Medici was eclipsed by that of the Venus de Milo, promoted (although inaccurately) as an exemplar of this style. But throughout the century, popular discourses cited both sculptures as icons of the ancient Greeks’ highly attuned artistic sensibilities and their superior, bygone physicality.

[5] G.F. Watts, 'On Taste in Dress', Nineteenth Century, 13, March (1883), 45–57; reprinted in Mary Seton Watts, George Frederic Watts: the Annals of an Artist’s Life, vol. 3 (London: Macmillan and Co., Ltd, 1912) pp. 202-227; see especially pp. 206-8.

[6] Mary and George were both vice-presidents of the Healthy and Artistic Dress Union. Elaine Cheasley Paterson, ‘Decoration and Desire in the Watts Chapel, Compton: Narratives of Gender, Class and Colonialism’ Gender & History, Vol.17 No.3 November 2005, pp. 714–736; see also Rhian Addison and Hilary Underwood, Liberating Fashion: Aesthetic Dress in Victorian Portraits, exh. cat. Watts Gallery—Artists’ Village, 16 February-7 June 2015.

[7] Ken Montague, ‘The Aesthetics of Hygiene: Aesthetic Dress, Modernity, and the Body as Sign,’ Journal of Design History Vol. 7, No. 2 (1994), pp. 91-112.

Text by Dr Melissa Gustin

|

|